Today we’re featuring Steph Speirs, clean energy entrepreneur, strategic advisor, board member, and public speaker.

Know someone who should be featured? Email us: info@echocomms.com.

About Steph: Steph recently co-founded and was CEO of Solstice, an enterprise dedicated to radically expanding the number of American households that can take advantage of clean energy using community-shared solar farms. She teaches climate tech at Yale School of Management and is a resident fellow at the Center for Business and the Environment. She serves on the boards of directors of the Sierra Club Foundation, Vote Solar, and Clean Energy for America, and on the Credit Committee of the Community Investment Guarantee Pool. Steph advises philanthropists, investors, companies, and keynotes on the future of climate tech and clean energy, entrepreneurship, and community benefits.

Her previous work includes leading solar sales initiatives in India at d.light, launching Acumen’s renewable energy strategy in Pakistan, shaping Middle East policy at the White House National Security Council, and field organizing in seven states for the first Obama presidential campaign. Steph holds a B.A. from Yale, a Master in Public Affairs with distinction from Princeton, and an MBA from MIT with a Certificate in Entrepreneurship and Innovation. She has been recognized with many honors including the EY New England Entrepreneur of the Year, US C3E Entrepreneurship Award, Elle Magazine and INCO’s US Impact Entrepreneur of the Year, and Grist 50 Fixer.

We spoke with Steph over email this week:

How did you first get into the clean tech industry? What inspired you to start your company?

Steph Speirs: Prior to clean tech, I worked on national security in the Middle East with the White House. While traveling through Yemen, I witnessed how attacks on oil infrastructure left ordinary people waiting in long lines for fuel, struggling to power their daily lives. I realized foreign policy discussions overlooked access to reliable energy, so I went to policy and business school to study clean energy. Initially, I started working on off-grid renewable projects in India and Pakistan.

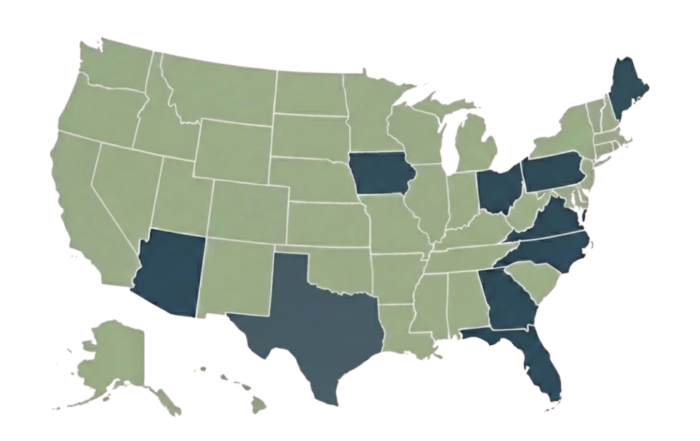

Eventually I came home to co-found and lead Solstice, which works to put affordable energy in reach of every American through community solar projects. We developed software to manage the customer experience for solar developers—maintaining a 98% subscription rate and 99% collections rate. We also created financing innovations that made community solar more inclusive, such as a Community Benefit Fund for low-income communities that Microsoft supported and an alternative credit score supported by DOE and Google that is more accurate in determining repayment and more inclusive than FICO credit scores.

A couple of years ago we sold the company to Mitsui, the Japanese conglomerate and global infrastructure player. After integrating with our parent company, I recently transitioned out of the organization, and the excellent management team has continued to grow the company.

Now I’m serving on boards, advising climate investors and companies, and teaching climate tech commercialization at the Yale School of Management.

What is the biggest challenge facing climate tech companies today?

SS: It took 60 years for oil, coal, and gas to reach mainstream adoption. It took 200 years for the price of cement to drop to be as low as it is. We don’t have that time to solve climate change, so climate tech companies need innovations in finance and policy to accelerate cost decreases in order to be competitive with incumbents.

The current unnecessary political crusade against climate makes it harder for American companies to compete globally. Projects cost more because of tariffs, and capital is contracting.

Investors already pulled back on climate funding starting in 2022, so they’ll maintain a high ROI and profitability bar for their investments even though they have $82B in dry powder. R&D-heavy and capital-intense businesses will have the hardest time. Climate technologies like geothermal, nuclear, carbon capture, critical minerals, and anything AI-enabled will have it easier in this environment.

The climate tech companies that can emerge from this moment will have to secure 18-24 months of runway, or cut non-essential spending, or shift their strategy to optimize for reaching profitability, or perhaps raise capital on less-than-ideal terms. They’ll focus their messaging less on climate and more on jobs, manufacturing, national competitiveness, economic prosperity, and energy security until the storm passes. Inevitably, it will pass. The demand for climate solutions will only grow over time.

What’s the biggest risk you’ve ever taken?

SS: Leaving the White House to start as an intern in a new industry in Pakistan and landing in the country without a place to stay. Or starting a for-profit business that prioritized low-income customers. Being underestimated can be scary, but I’ve learned to see it as an opportunity.

What’s something about you that might surprise people?

SS: I’ve spent the last five years learning to hunt and spearfish to source sustainable meat. As a meat-eater who works in climate, I was looking for a way to wean off the industrial meat industry because it’s responsible for so much of the food system’s carbon emissions, deforestation, and water use. The climate conversation about meat is so binary (are you vegan or are you evil?) and it doesn’t recognize the fact that meat and fish are also a part of so many people’s ancestral identity, including indigenous ones. Hunting and spearfishing have taught me that when we take care of the land, it nourishes us in return.

Know someone who should be featured? Email us: info@echocomms.com.

Check out our recent insights and conversations:

Sign up for our newsletter

Receive updates on our work, industry news, and more.